People

- People

- Hits: 8480

Studio Zaven

Founded in Venice in 2006 by Enrica Cavarzan and Marco Zavagno, Zaven is a multidisciplinary studio that combines design, communication and art, creating projects that are both creative and functional, with a unique identity and artisan roots, the result of a continuous blend of logic and instinct, rules and chaos. Enrica loves chopping boards and classic wines, Marco loves pitchers and surgically slicing vegetables, and one of their best projects together was inspired by an egg. Studio Zaven’s designs have been exhibited at the Triennale di Milano and art galleries in London, Paris and Istanbul, but the real secret is that all their ideas are born in the kitchen, the heart of their home. Despite their young age, Enrica and Marco have worked with both Italian and international institutions, in art and industry, with brands including Nike, Mercedes Benz, Red Bull, Telecom Italia and Tod’s, putting their creativity to good use.

How did you come up with the idea of Studio Zaven?

EC: We met when we were both studying at IUAV in Venice, but then took very different paths – Marco with Fabrica and Benetton, then in Spain and me with art and graphics for institutions. At a certain point we fell in love and moved in together, and that’s when we started working together. We both had our own jobs, but since we inevitably started influencing each others work, we thought: why not combine our efforts, strengths and skills?

Many designers end up living in their studios or transform their homes into studios, organizing parties and dinners in the midst of their projects. Is this something you’ve done?

MZ: No, we have always tried to keep the two separate. We found an independent studio far from where we live so we can separate work from our family life. We felt the need to have two different spaces, also to avoid conflicts and to set limits. Our kids made this a must. Before they came along, we could always sleep over at the studio, now things are different. Although the truth is, it’s almost impossible to truly separate the two areas when you work together…

EC: In the end, all our projects are born in the kitchen, after we’ve put the kids to bed and cleaned up. In fact, our new house is designed around the kitchen, which for us is an essential meeting place. It’s the place where we reload and work simply becomes a pleasure.

In your opinion as designers, what is the most homely object?

EC: For me, the perfect symbol of conviviality is the chopping board! At dinners we always put everything on platters to share, at the center of the table.

MZ: I agree, and I would add the pitcher. It’s an object we adore and have studied a lot, which is almost like the drinking equivalent of the chopping board, the container that distributes wine to other diners.

What’s your favorite wine? Have you ever thought of designing wineglasses?

EC: I like simple and classic wines, such as Sauvignon. It must be said that wine in Venice is democratic, where you can get a glass for a euro even if this means a headache the morning after. But this will never change.

MZ: If I have to be honest, I prefer beer, but this year for the first time we designed glasses for Arc on a large-scale and are waiting for the prototypes, nothing too special, but still a novelty for us.

Wine and food are two different yet related items, one fluid, the other solid, and have different forms and presentations. What do they mean to you and how do you see their relationship?

EC: I love traditional cooking and simple everyday food, but when I go out for dinner I like to experiment and try unexpected combinations. I enjoy food as an experience of discovery, both

visually in terms of the plate’s composition and the synergy of tastes that meet. In some starred restaurants, food becomes a real project, a construction. Then at home we like cooking together, it’s time for us, when we can relax.

You both have origins in Veneto, a land renowned for its wine. How has this landscape influenced your work? How has it taught to you design and create your region?

EC: More than Veneto, we are inspired by the whole of Italy. Obviously in Veneto there are outstanding artisans of all types, including Venetian glassmakers. Let’s just say that there are

great logistics and excellent manufacturers who make prototypes for the whole world, so why shouldn’t we take advantage of this?

MZ: Artisan production is very important and has won us the most awards, but we have also worked extensively with industrial manufacturing. In the end, each individual project is what

counts, but our roots have also been instrumental in our evolution as designers.

Your have a very strong relationship with craftsmanship, even participating in an exhibition entitled The Future is Handmade with your Pila vases. How do you reconcile the past and the future?

MZ: We adapt our various projects according to the client and their production system, but the underlying concept doesn’t change. If we work with an American multinational, we naturally approach the job differently to how we would with an artisan from Veneto, yet we try to keep the dialogue between these two realities open.

EC: The Pila series combines these two dimensions in a unique way, because it was born from an artisan background then adapted to the industrial world through the creation of moulds. This being said, the first ten pieces were made by us. We visited this amazing craftsman, Antonio Bonaldi, who works at the wheel and

constantly pursues his quest for perfection. At the time he was doing so by reproducing an egg. We commissioned a perfect cylinder, but then tried to give it some random movement, like a stack of books accumulated on a table. We were looking for the insanity of perfection linked to chaos.

MZ: The potter’s wheel can achieve perfection because the form is created around a rotating axis and is always smooth and perfect. We would like reality to be the same, but it never is, there is always an unexpected variable. So our shapes are inspired by perfection, but seek spontaneity. We want to translate this idea to the project. Almost perfect forms, always different, that represent the ordinary.

How do your projects take shape?

MZ: Each project has its own story and its own design; we try not to make any distinctions in advance. Production techniques teach you to think outside the box and to take different paths depending on the limits of industrialization, but it all depends on how the user perceives the object. Objects convey emotions. You can spend five euro and buy a jug from Ikea or spend 50 and have a handmade pitcher. Often objects are not only chosen because they are necessary or cheap, but because you fall in love with them and see a memory in their shape. We try to work with these ideas of forms, memories and meaning, which is at the basis of everything. Then if we are able to apply this tailor-made concept on an industrial scale, all the better. Even though these objects are handcrafted, they are not just for the elite, they are affordable. Then there is the question of finding the right form, the meaning that makes you want to purchase the object.

EC: Our studio is characterized by the tailor-made concept, not only because we target a niche market, but also because at a design level we are very attached to each individual project.

Our work is very diverse, but always specific, our projects are all in the same boat and joined by the same thread.

Venice is a city with a very strong and unique identity, what made you choose it?

MZ: I’m from Trieste and Enrica is from Castelfranco Veneto. It was the natural choice. Most designers are based in Milan, but we decided to stay here, even if Venice is a complicated city.

Despite being an island, thanks to the Biennale and other major foundations, it offers international exposure without losing its authentic local identity.

EC: Venice is beautiful and magic and still has this neighborhood feel to it, its habits are part of a life that we aren’t used to any more and that we don’t really want miss out on.

What, if any, has been your favorite project? Perhaps one that was particularly difficult to realize?

EC: One was definitely the pitcher. We kept thinking of these jugs, we designed at least eight hundred, maybe a thousand, but we were never able to unite the two shapes, the grip and the pitcher, the container and the handle. We had the idea of serving from a bottle.

MZ: In the end we cut everything back to the essential, simply attaching a handle to a bottle, as it is. It was probably the most basic and obvious solution, when you think about it, but without designing anything new, we took the archetypal shape of the bottle, attached a handle, and from two ancient forms we created something different.

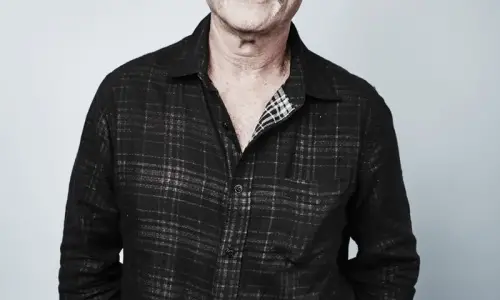

An interview with Enrica Cavarzan e Marco Zavagno

Words Lucia Brandoli Bousquet

Photography Claudia Corrent